Introduction: The Gorgon in the Mirror

Medusa, one of the most enduring figures from Greek mythology, has long been cast as a terrifying monster—a woman cursed to turn anyone who meets her gaze into stone. Her image, from ancient vase paintings to modern horror films, evokes fear and revulsion. Yet beneath the surface of this fearsome myth lies a story more intricate, more emotionally charged, and infinitely more human. A tale of violation, transformation, and exile, Medusa's myth encapsulates the historical anxieties surrounding feminine power and bodily autonomy.

To call Medusa a monster is to speak from the voice of the victors—those who have wielded myths as tools of social conditioning. But when viewed through a feminist lens, the myth splinters, revealing a wounded girl beneath the gorgon’s mask. Her story is not just about horror; it is about survival. About what becomes of a woman when her beauty is taken as provocation, her trauma as guilt, her power as threat. Feminist thinkers, artists, and writers have peeled back the mythological layers to uncover a figure who embodies not only vengeance, but vulnerability; not only rage, but resilience. This essay will explore the shifting representations of Medusa, examining how feminist reinterpretations challenge patriarchal narratives and illuminate the complex interplay of gender, power, and otherness

The Full Myth of Medusa: From Maiden to Monster

Medusa was not always the feared Gorgon of popular imagination. In early tellings, particularly in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, she is described as a stunningly beautiful mortal woman, the only one of three Gorgon sisters who was not born a monster. Her beauty was so striking it caught the attention of Poseidon, god of the sea, who raped her in the temple of Athena. This act of desecration was not met with punishment for the god, but instead fell squarely on Medusa. Athena, enraged by the violation of her temple—not by the crime against the woman within it—transformed Medusa into a Gorgon with serpents for hair and a gaze that turned men to stone.

This origin story sets the tone for centuries of mythic injustice. Medusa’s transformation from a human girl to a monster is not one of guilt but of blame displacement. She becomes a scapegoat, her monstrosity functioning as a divine smokescreen for patriarchal violence. Exiled to a remote island, she is hunted not for her actions but for what she has become—a woman whose body and gaze are considered lethal simply because they are no longer controllable.

Her death at the hands of Perseus completes this narrative arc of domination. Sent to kill her with divine tools and tricks, Perseus uses Athena’s reflective shield to behead her while she sleeps. Even in death, Medusa is exploited. Her severed head becomes a weapon wielded by Athena herself—a grotesque trophy pinned to her shield. Medusa’s image is weaponized, her story erased.

And yet, from her blood springs Pegasus, a creature of beauty and inspiration. This paradox—death giving birth to poetry—suggests that Medusa was never just a monster. She was always more. She deserved more.

The Myth and Its Violence: The Girl, the God, and the Silence After

Before the snakes. Before the statues. Before the silence that wrapped around her like stone—Medusa was a girl. A mortal among immortals, a priestess in Athena’s temple, she was revered for her beauty, yes, but more than that—for her devotion. She gave her life to the gods, walked in the still corridors of sanctity, whispered prayers into marble halls, believed that obedience and reverence would shield her.

But myths rarely honor the faithful.

Poseidon, god of the sea, tempestuous and entitled, found her. Found her and took her, not in love but in violence. Not in seduction but in violation. There, within the sacred space where Medusa sought protection, the ocean broke into her body. No waves crashed—only silence, terrible and holy. What followed was not only the loss of innocence, but the theft of meaning. And what did Athena do? Not vengeance on the god. Not justice for the girl. No divine fury hurled at Poseidon. Instead, punishment fell on Medusa—as if the sanctity of the temple mattered more than the sanctity of the girl. The goddess transformed her. Not to empower, but to exile. Not to protect, but to erase. Her hair twisted into serpents, her gaze made fatal, her once-loved beauty turned against her like a blade. She was marked, not by the violence done to her, but by the story the world chose to tell about it. This is the violence of mythology—it disguises trauma as destiny, masks cruelty as cosmic order. Medusa was rewritten, not remembered. She was no longer the girl in the temple. She became the thing in the cave. The danger. The warning. The monster.

And yet… what was monstrous?

Not the girl who had been wronged, but the society that turned her pain into a horror story. What was truly frightening wasn’t her power—it was her proof. She carried evidence of divine injustice on her body. The serpents hissed the truth that no one else would speak: that power protects itself, not the innocent. Every hero that came to slay her came not to liberate but to silence. Perseus didn’t see a woman. He saw a trophy. A head to be used, not a voice to be heard. He crept into her solitude with mirrored shield and blade. He didn’t look her in the eye—he couldn’t. Not because she was evil, but because she reflected something unbearable. The pain they inflicted. The guilt they buried. They said her gaze turned men to stone. But maybe they were already stone—rigid in their fear, immobile in their cruelty. Maybe Medusa’s eyes didn’t petrify. Maybe they revealed. Maybe they demanded you to look. Really look. At what was done. At what was denied.

And they couldn’t bear it.

Medusa’s myth becomes a mirror—one held up to a world that punishes women for the crimes committed against them. A world that calls them monstrous for surviving. That tells them: silence is safety. Disappear, and we’ll forget. Speak, and we’ll make you myth. But myths forget the girl. They forget the trembling. The pleading. The altar before the assault. They remember the snakes, the glare, the stone. They forget the woman. We must not. Because Medusa deserved more than fear. More than punishment. She deserved to be mourned. To be remembered as human. She deserved someone to name the god’s crime—not her form—as monstrous. She deserved a mythology that asked: What do we do with our wounded? instead of How do we contain them?

She deserved better than legend. She deserved love.

Feminist Reclamation: Rage, Rewriting, and Recognition

Feminist thinkers and writers have taken Medusa’s story and wielded it like a mirror reflecting centuries of gendered violence, silencing, and erasure. Hélène Cixous’s groundbreaking essay, “The Laugh of the Medusa,” doesn’t just ask us to see Medusa differently; it invites us to feel her truth viscerally. Medusa is no longer a mythical monster but a woman who embodies the disruptive power of female rage and the radical honesty of seeing the world as it is—painful, unjust, and fiercely alive. Cixous calls on women to find their own Medusa within—not as a beast to fear but as a powerful self who dares to confront, to laugh, to reclaim voice and agency long denied.

But this reclamation is not a gentle softening or sanitization of her myth. It is a raw reawakening that honors both her rage and her vulnerability. It asks us to hold space for the messy complexity of trauma and power—how rage can be a balm, a survival mechanism, a way to rewrite a narrative that tried to silence her. Feminist reinterpretations let Medusa bleed and blaze in full color, refusing to reduce her to a mere symbol of monstrosity. Instead, she becomes a fierce emblem of resilience, a reminder that rage itself is a form of knowledge, an embodied truth that cannot be erased.

Beyond Cixous, thinkers like Judith Butler explore how Medusa’s monstrosity is a performance imposed by a society that fears unruly femininity—how her gaze, once punished, now exposes the fragility of patriarchal power. Julia Kristeva’s theory of abjection deepens this by revealing how Medusa embodies what society casts out and fears: the messy, corporeal, uncontrollable aspects of the feminine. Feminist scholars like Silvia Federici further illuminate how Medusa’s punishment is emblematic of the historical control of women’s bodies and desires, a violent policing of female autonomy disguised as moral order.

This intellectual reclamation pulses with emotional intensity. It is a reclaiming of the fractured self, a stitching together of pain and power into a new mythology. Medusa is no longer merely a figure of fear but a beacon for anyone who has been silenced, shamed, or made monstrous for asserting their existence.

Her story, once told only in whispers and warnings, now roars in feminist discourse—demanding recognition, demanding justice, demanding a world where the Medusas among us are seen not as threats to be destroyed but as humans to be understood and embraced.

Medusa in Art and Literature: Bearing Witness through Creation

Art and literature have always held space for what the world is unwilling to see, and Medusa has become a powerful conduit for feminist expression. Her image, long used to instill fear, now becomes a canvas of reclamation and witnessing.

Louise Bourgeois’ sculptures, marked by their raw emotionality, reimagine Medusa not as a solitary figure but as a mother, protector, and survivor. The writhing forms suggest both pain and resilience, inviting us to see monstrosity not as aberration but as a byproduct of suffering that demands acknowledgment.

In poetry and prose, Medusa speaks back. Adrienne Rich, Sylvia Plath, and Carol Ann Duffy all invoke her image to articulate the unspeakable—the disquiet beneath feminine decorum, the scream stifled by centuries of silence. Duffy’s poem "Medusa" does not romanticize her; it instead dwells in her pain, her decay, her heartbreak. It is a meditation on love, betrayal, and self-loathing—a psychological portrait of a woman turned inside out by grief.

These creative works suggest that Medusa’s myth is not one of finality but of possibility. To bear witness through art is to declare: we see her. And in seeing her, we begin to see ourselves.

#MeToo and Medusa: The Modern Gaze

In the wake of the #MeToo movement, Medusa’s image has returned with urgent resonance. Once again, we see women telling their stories only to be doubted, ridiculed, or punished. The parallels are chilling: a woman speaks, and society flinches. She accuses, and suddenly she becomes dangerous. She is no longer human—she is mythologized, demonized, erased.

But in feminist circles, Medusa has become a rallying figure. She adorns protest signs, tattoos, and zines. Her image symbolizes a kind of solidarity that emerges when women refuse to be shamed into silence. Sculptor Luciano Garbati’s famous piece, which reverses Cellini’s classical statue by showing Medusa holding Perseus’s severed head, flips the power dynamic. It is not a call for vengeance but for visibility, for justice, for narrative sovereignty.

In this moment, Medusa’s story is reclaimed not just as a metaphor, but as a mode of political being. To channel her is to embrace complexity: fury, fear, resilience, defiance—all coiled into a single gaze.

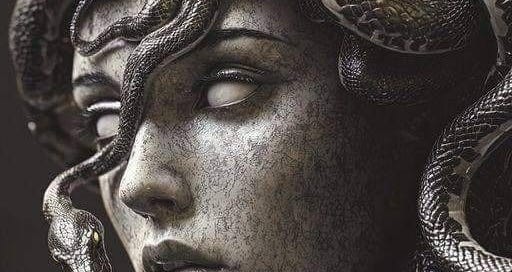

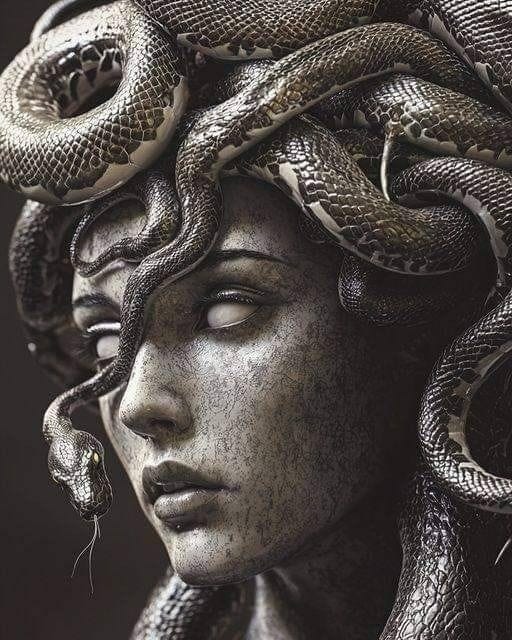

Beauty and Monstrosity: Redefining the Gaze

Medusa’s physical transformation—from beauty to beast—forces us to question our aesthetic biases. What is beauty, and who decides it? If beauty is a currency, then Medusa is the woman who dared to counterfeit it. Her snakes, her petrifying gaze, her uncontained femininity—all of it stands in opposition to the idealized, domesticated female form promoted by patriarchal cultures.

Her monstrosity is not her failure, but her resistance. She defies consumption. She does not seduce; she confronts. She stares back.

To find beauty in Medusa is to find power in what has been cast out. It is to recognize that monstrosity is often a projection—an accusation hurled at those who refuse to conform. Her face, once feared, becomes a shield against erasure. Her story becomes a space in which women can reimagine not only themselves, but the very contours of femininity.

Conclusion: Serpent-Crowned Sovereignty

Medusa’s story is not simply a tale of transformation—it is a testament to the politics of mythmaking. For centuries, her silence has echoed louder than her screams, her image wielded as a tool of fear. But in the hands of feminist thinkers and creators, her story becomes an anthem. An elegy. A manifesto. She ceases to be a monster. She becomes a mirror. In reclaiming Medusa, we reclaim the parts of ourselves that were once too loud, too angry, too unlovely to be accepted. We embrace the serpents. We lift our heads. We let the gaze return.

To stand with Medusa is to stand in the ruins and rebuild. Not a temple to fear, but a sanctuary of truth. She is not the end of the story. She is the beginning of the reckoning.

Till next time, Mukta<3